If I ever defected to another country, I would escape to Shondaland. In fact, I must admit I already escape into the world of Bridgerton whenever the cray-cray of this present darkness overwhelms. The Shonda Rhimes Netflix franchise, based on the historical romance series by Julia Quinn, follows the love lives of eight tight-knit siblings of the influential Bridgerton family within a fully integrated Regency era Britain. This royal lot and its court (known as “the ton”) stroll and quadrille and duel and love in a world where non-traditional casting is not so much fantasy as it is spectacular. The precarious position of the ton’s residents of color is acknowledged in both Bridgerton seasons, yet never explained—until Queen Charlotte, Shondaland’s blockbuster Netflix prequel written by Rhimes herself. Rhimes’s explanation of the racially bridged ton stretches modern imaginations to conceive a past we never lived; forcing us who sit in a divided and entrenched America to reckon with the possibility of the impossible—a world without racial hierarchy. All we need is to choose it.

In Shondaland’s Queen Charlotte, women and men of African descent rise into their (our) full humanity and flourish. She weaves a world where historical shame (our melanin-rich skin and our form-holding hair) is transformed into our crown and glory.

Queen Charlotte, which toggles back and forth between the current world of the Bridgertons (circa 1810s) and the 1760s world of young Charlotte, begins with a caveat: This story is not history. It is fiction, inspired by fact. There was, indeed, a British queen whose blood stretched back to Africa. She ruled. She loved. She was the grandmother of Queen Victoria. That, Rhimes posits, is fact.

In fact, according to scholars, Charlotte was not the first Queen of England whose ancestry stretched to Africa. Queen Philippa (born 1310) married King Edward III at York Minster on January 24, 1328, eleven months after his accession to the English throne. Her ancestry is believed to have hailed from England, Holland and The Moors. The Moors of Mauritania (just above Senegal) and Northern Africa had conquered and ruled within the Iberian Peninsula from 711 to 1492 (700 years). During that time, they intermarried and blended into every level of European society. This is the reason Shakespeare could reference Othello, the Moor General of Venice, without controversy in Shakespeare’s day.

England was established by Normans who came up from the Iberian Peninsula in 1066—smack in the middle of Moorish rule. Thus, people of African descent entered England in the days of William the Conqueror, not as enslaved chattel, but as a ruling class.

But by the time of young Queen Charlotte, the African Slave Trade had grown with the British empire. When she ascended to the throne in 1761, slavery was legal inside Britain and remained so for another eleven years. After 1772, the British empire maintained its enslaving colonies such as Barbados, Jamaica and the British West Indies and became the first slavocracy to outlaw the Transatlantic slave trade in 1807—during Queen Charlotte’s Regency-era rule.

While Shonda’s rendering is not history, there are juicy historical facts embedded throughout the story. On the lighter side, by all accounts King George III and Queen Charlotte truly were in love. In fact, George was the first King of England not to pursue extramarital affairs. He really did build Buckingham House for her and the two really did live at Kew, now known as Kew Gardens, in the summer months. There “Farmer George” oft burrowed his hands in the dirt alongside his gardening queen. As well, minutes into episode three Queen Charlotte proclaims to her attendants who are hanging decorations on the Christmas Tree: “More color! The whole tree should have more color! I have been saying this for years. It is a festive tree.” Queen Charlotte, hailed from Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Germany. One gift she brought the British from her homeland was the German Christmas tradition of the Christmas tree.

But in Shondaland, a single act of agency by the Palace opens a universe of possibility inaccessible to the harsh landscape of Princess Meghan Markle’s derision. Contemporary accounts of Queen Charlotte say she was of a darker hue. Her nose was broad and her lips were thicker. In addition to descending from German royalty, Queen Charlotte descended from a Portuguese royal and his mistress—who was a Moor. There is a moment in episode one when King George’s mother, Princess Augusta, sits with members of parliament who talk of the Queen’s skin color.

“She is very brown,” says the Princess.

“I did say she had Moor blood,” her aid responds.

“You did not say she would be that brown,” retorts the Princess.

“It is a problem. People will talk,” declares Prime Minister Lord Bute. The lot agree.

After a long pause, Princess Augusta, declares in a flash of brilliance: “We are the palace. A problem is only a problem if the Palace says it is a problem.”

From thence forth the lot embark on the fictional “Great Experiment” of racial integration within the ton. Subjects of color are elevated into the Court; given lands, money and (eventually) access equal to those granted to white courtiers. This palatial choice to exorcize the demon of racial hierarchy by exercising its own power is where Shondaland and reality part ways.

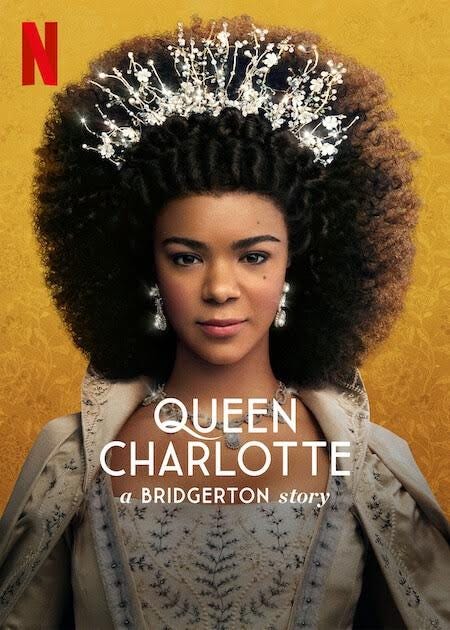

In Shondaland the palace decided to change perceptions of Blackness through conscious restructuring of society and redistribution of wealth and power. But it does not all come easy. Even after initial structural changes, the Princess demands that Charlotte shrink herself and mute her glory to fit into current simpler British fashion. But Charlotte rebels. She dons her own spectacular custom-made wedding gown and emancipates her hair from its plain puff; fanning out her afro into its full-blown glory.

This Rhimesian moment lives so outside of our collective imagination that a single utterance threatens to make the moment go poof. Ethereal music titled, “A Feeling I’ve Never Been,” carries Charlotte forward toward her George. She hesitates under the disapproving scowls of white women and the grimacing distain of white men. She continues forward.

I am reminded of my own first days immersed in white community. Without ever hearing the word, assimilate, I found ways. I cut bangs and curled them with a curling iron every morning. By the time I returned home from school my “bangs” would be a single frizz puff on my forehead or, if I was lucky, they would stretch straight out over my nose, like a diving board over a pool.

“Well, at least they’re straight,” I would reason.

I did everything I could to “fit in”—each assimilation tactic inched me further away from my African-descended self and the divine power of my heritage. Eventually, Lisa, daughter of SNCC member, Sharon, and Caribbean descended father, Dennis,—Lisa, grand and great-grand daughter of the Great Migration and survivors of enslavement and Jim Crow—Lisa, whose blood stretches back to Senegal and Nigeria and Benin and Togo and Cameroon—that Lisa lay hidden beneath layers of simulated whiteness and black shame. Now, snatched back to those memories, I am transported to a time when I did not understand my own power—my own glory. Rather, I allowed whiteness to set the conditions of my belonging.

So, as I watch Charlotte’s afro negotiate the catwalk of St. James’s Chapel Royale for the fifth time, I feel a feeling I had never been. Charlotte steps forward through regal protectors of white power. When she steps onto the stage and takes the hands of her smiling George she matches power with power—the divine power of unabashed Blackness. And that’s just the beginning.

Originally published on Freedom Road here.

President and founder of FreedomRoad.us, Lisa Sharon Harper is a writer, podcaster and public theologian. Lisa is author of critically acclaimed book, Fortune: How Race Broke My Family And The World—And How To Repair It All.

Connect

Connect with Lisa: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Linked In

Connect with Freedom Road: Institute Courses | Patreon | Substack